Lehigh Valley Geology Field Trips

Field Trip 2, Stop 3

Deformational Features Within the Martinsburg Formation

Caution: The exposure along PA Route 248 is a exposure along a highway on which drivers often speed as they descend a long grade. Use extreme caution when crossing this highway.

(Click on images to enlarge)

(Source: DeLorme 3-D TopoQuads)

The exposure involves two locations in Beersville separated by about 300 meters (about 280 yards). Stop 3A is along PA Route 248 and stop 3B is along the minor road that is perpendicular to PA Route 248 at Beersville.

(photograph by the late Dr. Richmond Myers)

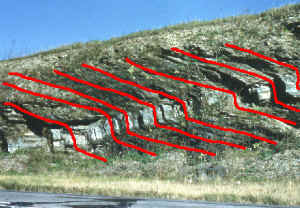

Stop 3A along PA Route 248. The beds are composed of the Martinsburg Formation (the "Martinsburg Shale"), which is Ordovician in age (505 to 438 million years), but occurs stratigraphically above the "Jacksonburg Limestone," which was seen in the previous stop. Thus, the Martinsburg is younger than the Jacksonburg. The beds strike into the exposure and dip to the left, as can be seen by the more competent sandy bed that lies between the more shaly upper and lower units. Foliation is seen to appear as an open "Z" in the above photograph, refracting in orientation within the sandy bed to be almost perpendicular to the bedding.

These rocks formed during the Ordovician Period (505 to 438 million years ago) in deep marine waters, probably off the continental shelf. Underwater avalanches of sediment, called turbidity currents, probably brought much of this clastic material to add to the growing thickness of shale, impure sand, and sandy shale that would become the Martinsburg Formation.

Same picture as below with faults and fault movement shown.

(photograph by the late Dr. Richmond Myers)

Stop 3A shows a continuation of the above picture and shows two faults that run in an open "Z" shape from upper left to lower right. The displacement of the sandy bed (not easily seen in the picture) indicates reverse faulting. Both that, and the imposed foliation, are testimony to the post-depositional compressive deformation that was imposed upon these rocks as part of the building of the Appalachian Mountains.

The pictures above were taken by the late Dr. Richmond Myers in 1960 and show the exposure with less vegetation than it now has. Except for the vegetation differences, the exposure is relatively unchanged.

Stop 3B is in a "borrow pit," probably used for local road construction. The rocks here are the sandy beds of the "Martinsburg Shale" and are similar in composition to the sandy bed seen in stop 3A above. However, here they are folded into a recumbent fold -- one that has been overturned. Indeed, the deformation is so severe that the identity of the fold -- anticline or syncline -- is undetermined. Lines have been drawn along the bedding planes on the photograph to better reveal the recumbent folding.

The photograph above shows the ame exposure, slightly enlarged and enhanced. Here holes made by a rock drill are in evidence both above and below the fold axis. Most likely these holes were made to test the rock for their paleomagnetic information: to determine the orientation of the Earth's magnetic field when these rocks were deposited horizontally during the Ordovician Period, and consequently to be able to compare the geometry of the paleomagnetic orientations with those determined from the structural orientations.

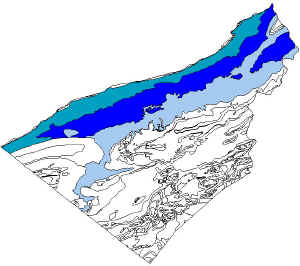

(Source: ArcView GIS Software)

The map above shows the distribution of the Martinsburg Formation within Lehigh and Northampton counties. All other rock units are shown as white. The darkest blue is the sandy member of the Martinsburg Formation and tends to make a higher topographic surface than the less-sandy shales (the lighter blues) on either side of it. Slate is quarried from the areas where the shale is relatively free of sand. The northwestern margin also has exposures of sandy shale, but this rock unit has been given a different formational name, so it has been left white on this map.

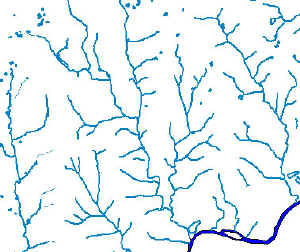

(Source: ArcView GIS Software)

The Lehigh Valley area receives an average of approximately one meter (40 inches) of precipitation per year. Because the Martinsburg Shale is insoluble, the water runs off on the surface, producing the integrated surface drainage pattern that is portrayed on the map above. The area shown on the map is within the Lehigh/Northampton County border in the Bangor region, which is near the eastern boundary of the map above. A portion of this area has been glaciated in the most recent advance of the continental icecap. The Lehigh River is the major stream that flows across the bottom right of the map.

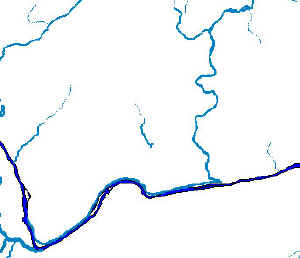

(Source: ArcView GIS Software)

Tributaries are lacking over the limestone/dolomite bedrock. In contrast to the drainage that is developed over the shale, the surface drainage is almost absent over the limestone/dolomite bedrock areas of Northampton and Lehigh counties. Precipitation that falls on the limestone/dolomite bedrock drains through the soil and into cracks and crevices within the soluble rock below. This percolating water dissolves the soluble rock as it flows underground. This groundwater discharges into local rivers through surface springs or by infiltration up through the bed of the river. The major river flowing parallel to the bottom of the map is the Lehigh River and the river flowing north to south, right of center, is the Monocacy Creek. The main campus of Moravian College would be on the map to the right of the Monocacy Creek. Major rivers and streams in this area, like the Lehigh and Monocacy, form on insoluble bedrock and flow on the surface through the region of soluble bedrock. The area portrayed on this map is approximately equal to the area portrayed on the previous map.

Related regional geological features NOT seen on these field trips.

This quarry, north of Bethlehem, shows folding of the Martinsburg Shale, here metamorphosed to a slate. Red lines are drawn to show the original bedding of the pre-slate shale to reveal the folding style of the deformation. Note the workman's shed at the quarry edge for scale. The black along the right of the photograph is a shadow from the quarry edge.

(photograph by the late Jack Weidner)

Slate is quarried from the Martinsburg Formation where the rock has been relatively free of sand because the sand interferes with the development of foliation. In general, the middle member of the Martinsburg Formation is sandy and is most resistant to weathering and erosion. This member of the Martinsburg Formation makes the higher elevations within the Lehigh Valley between Kittatinny Mountain ("Blue Ridge" to the locals) to the north and the South Mountain complex to the south. The upper and lower members of the Martinsburg are free of sand and are the preferred locations for the quarrying of slate. Thus, slate quarries are found north and south of the center of the surface exposures of the Martinsburg Formation, but not in the central region.

Slate splits along foliation, rather than the original bedding, into thin sheets. This preferred splitting allows it to be used for roofing material.

This sample splits preferentially along foliation, which runs from lower left to upper right, rather than bedding, which is marked by the dark/light color bands at about a 70-degree angle to the foliation in the sample shown above.

In the Lehigh Valley area it is not uncommon to find older buildings completely covered with slate, as is the building in the photograph above. That building is located along PA Route 191 (the "Nazareth Pike") at Newburg. Subsequent to the taking of this photograph, the sides of this building have been covered with aluminum siding.

(photo from Moravian Development office)

The roofs on the Moravian College main campus are composed of slate, most of which probably came from the slate quarries of the Lehigh Valley. Consequently, most of it would be the local Martinsburg Shale, which was metamorphosed to a slate. Comenius Hall is on the left of the photograph above.

The trim on the upper and lower edges of Collier Hall of Science consists of slate which is split along foliation. The slate was applied to Collier Hall of Science for architectural consistency with other buildings on campus.

The view shows Jacobsburg Park, which is north of Bethlehem near the Belfast exit of Pa Route 33. The scale of the photograph is provided by the bright yellow school bus that is in the park's parking lot. The Martinsburg Shale is well exposed in the deeply incised stream channels within the park. The Martinsburg Shale is insoluble and, consequently, has a well integrated drainage system of surface streams wherever it occurs

End Stop #3 of Field Trip #2

(all photographs by J. Gerencher, except for the one by the late Jack Weidner, the two by the late Dr. Richmond Myers, and the one by the Moravian Development Office)